THE SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION

And the prayer offered in faith will make the sick person well; the LORD

will raise them up. If they have sinned, they will be forgiven. Therefore,

confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be

healed. The prayer of a righteous person is powerful and effective. Elijah

was a human being, even as we are. He prayed earnestly that it would not

rain, and it did not rain on the land for three and a half years.

James 5, 15-17

The practice of confessing to a priest in the Catholic Church has its ancient roots in the traditions of Judaism, as illuminated by teachings and practices found in the Old Testament, particularly in the Book of Leviticus (4-6). The text reveals that ancient Jews brought sin offerings to a priest and confessed their sins to receive atonement and forgiveness. The process involved laying hands on the animal, which symbolized the transfer of the sin to the animal, followed by its sacrifice, where the priest would use the blood to atone for the sin. The specific animal and ritual depended on the status of the person confessing the sin. These offerings served as symbolic acts of repentance, representing a deep desire for forgiveness and reconciliation with God. The rituals described in Leviticus not only emphasize the importance of personal responsibility for one’s actions but also reflect the communal aspect of faith, where individuals are held accountable within the community of the faithful.

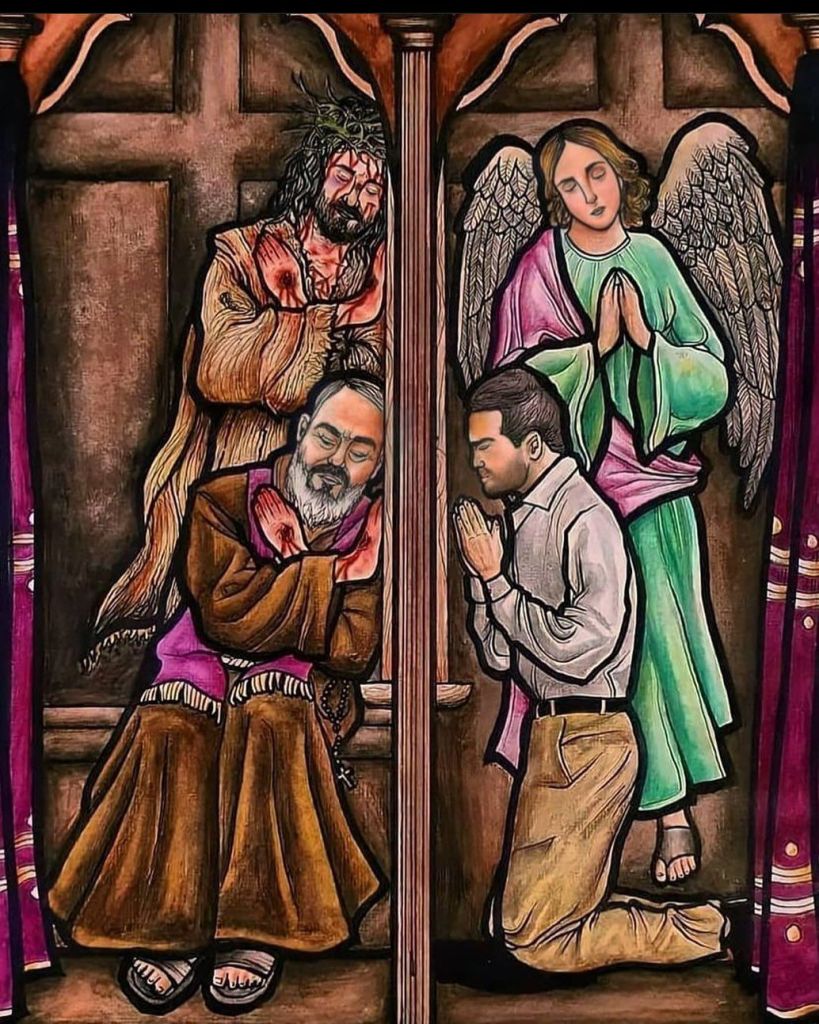

In Catholicism, this historical practice evolved into the sacrament of Reconciliation, also known as Confession. Here, believers openly confess their sins to a priest, who serves as a spiritual mediator acting in the person of Christ. This sacrament is steeped in theological significance; through the priest’s absolution, the faithful receive God’s grace and forgiveness. Through this intimate sacrament, individuals not only seek to mend their relationship with God but also find solace in the divine mercy offered through the Church. The act of confessing thus becomes a transformative journey—one that allows individuals to receive spiritual guidance, reassurance, and, ultimately, the strength to continue their path toward righteousness. The ritual fosters a deeper understanding of personal flaws and instills a commitment to moral growth, shaping the believer’s life in accordance with Christian teachings and values.

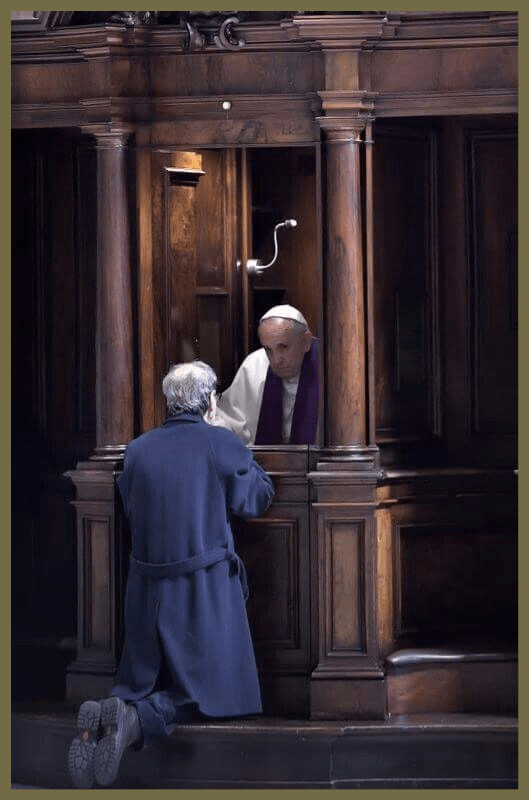

The Sacrament of Reconciliation involves several key steps: First, individuals examine their consciences to identify their sins. Next, they sincerely desire to amend their behavior and avoid these sins. The process continues with the confession of sins to a validly ordained priest, followed by the completion of a penance assigned by the priest. The primary purpose of this sacrament is to restore the individual’s relationship with God and to receive sanctifying grace, which aids in healing the soul and repairing that relationship. By participating in Confession, faithful Catholics can attain absolution for the sins committed against God and others, thereby re-entering into communion with the Church.

In the practice of Confession, Catholics are encouraged to reflect on and enumerate their sins, guided by their conscience. For a confession to be effective, it is essential to confess all mortal sins, which are also referred to as “deadly” sins (as noted in 1 John 5:17). These include any serious sins committed since the last confession, as well as any habitual sins that may arise. The Church mandates Catholics partake in confession at least once annually, ideally during Easter. However, the Magisterium strongly advocates for the faithful to engage in this sacrament more frequently, particularly when dealing with the gravity of mortal sins.

The text from James 5:15-17 emphasizes the decisive role of prayer and the importance of confession within the Christian community, particularly in the context of healing and forgiveness. This passage is often associated with the sacrament of confession, highlighting several key themes.

The opening lines express a promise that prayer offered in faith can lead to healing for the sick. This aligns with the sacrament of confession, where individuals seek spiritual and sometimes physical healing through the act of confessing their sins. In this context, confession becomes a means of restoring one’s relationship with God and receiving His grace. Moreover, the passage states that if the sick have sinned, they will be forgiven. This underscores the connection between confession and forgiveness. In the sacrament of confession, acknowledging sins is crucial, as it enables individuals to receive God’s mercy. The act of confessing one’s faults not only cleanses the soul but also prepares the way for spiritual and physical healing.

The text encourages believers to confess their sins to one another and to pray for each other. This highlights the communal aspect of faith. In the sacrament of confession, though the act is often personal, it takes place within a broader community. The Church, through the priest, acts as a mediator, facilitating God’s grace and forgiveness. Moreover, the act of praying for one another fosters a supportive community, reinforcing the idea that healing often occurs in the context of shared faith and accountability.

The reference to Elijah, a figure known for his earnest prayers, serves to illustrate the effectiveness of prayer when offered by a righteous or appointed person. This implies that those who are in right relationship with God have a special role in intercessory prayer. In the context of confession, it highlights the importance of a repentant heart and the transformative power of prayer in seeking forgiveness and healing.

And I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you.

And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh

and give you a heart of flesh.

Ezekiel 36, 26

Jesus emphasizes the importance of conversion as a key aspect of his message about the kingdom of heaven. According to Catholic teaching, baptism serves as the primary means for initiating this fundamental conversion. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states, “Baptism is the principal place for the first and fundamental conversion. It is by faith in the Gospel and by Baptism that one renounces evil and gains salvation, which includes the forgiveness of all sins and the gift of new life” (CCC, 1427). Through baptism, individuals are considered “washed, sanctified, and justified” (1 Cor 6:11). However, it is important to note that while baptism provides this initial cleansing and spiritual rebirth, it does not eliminate the inherent weaknesses of human nature or the tendency toward sin, known as concupiscence. As a result, baptized individuals must continue to rely on divine grace for their perseverance in faith throughout their lives.

Catholics believe that “Christ’s call to conversion continues to resound in the lives of Christians.” This daily need for conversion or “second conversion is an interrupted task of the Church, which is at once holy and always in need of purification, follows constantly the path of penance and renewal. The endeavor of conversion is not just natural human work. It is the movement of a contrite heart drawn and moved by grace to the merciful love of God who loved us first” (CCC 1428).

Interior conversion involves the genuine desire of “turning away from evil, with repugnance toward the sins that we have committed” as baptized Christians. Simultaneously, a conversion of the heart “entails the desire and resolution to change one’s life” or continue to grow in holiness despite the occasional backsliding. What makes doing penance fruitful is the “conversion of heart that is accompanied by a salutary pain and sadness” and the desire to restore equity of justice in our relationship with God (CCC 1431).

The passage from Ezekiel 36:26 speaks to a profound transformation that occurs in the heart and spirit of a believer, indicative of true conversion and reconciliation with God. At its core, this verse conveys God’s promise to restore and renew His people, moving them from a state of spiritual deadness to one of vibrant faith. The “new heart” symbolizes a profound transformation within one’s inner being. In biblical terms, the heart often represents the center of a person’s thoughts, emotions, and will. A “heart of stone” signifies a hardened state—one that is resistant, unfeeling, and detached from God.

This condition can result from sin, disobedience, or a lack of spiritual awareness. By contrasting this with a “heart of flesh,” the text indicates a softening and receptiveness to God’s love, truth, and purpose. God’s promise to give a “new spirit” further emphasizes the internal change that accompanies true conversion. This new spirit, empowered by the Holy Spirit, enables the individual to comprehend and embrace God’s will, fostering a deep desire to walk in His ways. This transformation is not merely superficial; it penetrates the very essence of who a person is.

Reconciliation with God is fundamentally about restoring the broken relationship caused by sin. By removing the heart of stone and replacing it with a heart of flesh, God facilitates a genuine connection with humanity. This process is liberating, allowing individuals to experience His grace, forgiveness, and guidance. As a result, those who undergo this transformation often feel an overwhelming sense of purpose and belonging in their relationship with God.

For after thou didst convert me, I did penance: and after thou didst shew unto me,

I struck my thigh: I am confounded and ashamed,

because I have borne the reproach of my youth.

Lamentations 2, 14

Lamentations reflects a deeply personal journey of conversion and the subsequent realization of one’s past sins. It captures the emotional turmoil that often accompanies a genuine transformation in one’s spiritual life. In this context, conversion refers to the process of turning away from previous ways of living that are seen as sinful or misaligned with one’s spiritual beliefs. The act of penance that follows conversion signifies a recognition of wrongdoing and a sincere desire to atone for those actions. The phrase “after thou didst convert me” illustrates the transformative power of divine influence or grace, indicating that it is through a higher calling that the individual acknowledges their need for change.

The act of striking one’s thigh can be interpreted as a gesture of deep remorse or grief. It is a physical manifestation of sorrow for past actions and represents a profound internal struggle. This moment signifies the confrontation with one’s own failings – the shame and “reproach of my youth” highlights feelings of regret and embarrassment over past misdeeds. Overall, the lamentation highlights an essential aspect of spiritual growth: acknowledging one’s shortcomings and accepting responsibility for them. It showcases how, through conversion, one can move from a state of confusion and shame to a place of awareness and a commitment to change. This journey emphasizes that true conversion is not merely a one-time event but a continuous process of reflection, repentance, and renewal.

Penance involves a heaviness of heart brought about by God’s co-operative grace that turns the heart of stone into a heart of flesh. It is God who takes the initiative and causes our hearts to return to him, but not without our co-operation (Lam 5:21). God gives us the strength to be renewed by the outpouring of His Spirit. Moved by the Spirit to repent, we confess our sins and make acts of reparation that are ultimately the work of the Holy Spirit, whom we have initially received in Baptism. It’s by the agency of the Holy Spirit that “our heart is shaken by the horror and weight of sin and begins to fear offending God by sin and being separated from Him” (CCC 1432).

In the context of reconciliation, it is important to note that the sacrament is not fully realized without accompanying acts of penance and restitution. These penitential actions are essential for achieving complete reconciliation with God, aligning with the principles of commutative justice. The sacrament encompasses three fundamental elements: contrition, confession, and satisfaction, which are crucial for the process of forgiveness and reconciliation (CCC, 1446-1449).

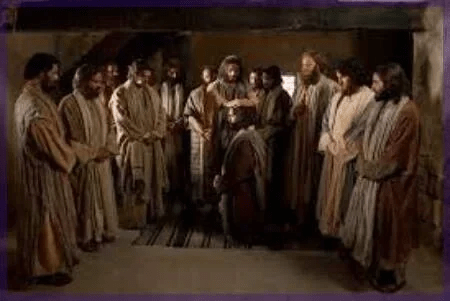

Jesus granted his apostles the authority to forgive sins. He said to them prior to his ascension into heaven, “As the Father sent me, so I send you” (Jn 20:21). As Christ was sent by the Father to forgive sins, our Lord commissioned his apostles and their ordained successors to forgive sins in his name. We read in the gospel that Jesus breathed on his apostles and gave them the power to “forgive and retain” sins (Jn 20:22-23). Jesus speaks of “the sins of any,” meaning the personal sins of individuals. From this phrase, we can infer that the penitent must first confess their sin to an apostle or successor of his in the ministry of the priesthood before their sin can be forgiven or retained, judging by the genuineness of conversion. Although he is a divine Person, Jesus forgave sins in his humanity through the power invested in him by his heavenly Father. He did this to convince the scribes and Pharisees that he had, in fact, the authority to forgive sins, though he isn’t the Father (Mt 9:6; Mk 2:10; Lk 5:24).

Jesus transferred this authority to his apostles, and they in turn to their appointed successors in the ministry or divine office. St. Paul forgives sins in persona Christi as a validly ordained minister (2 Cor 2:10). The “ministry of reconciliation” or the ministering of the sacrament was given to the “ambassadors” of the Church (2 Cor 5:18). Soon after returning from Jerusalem to Antioch, Paul and Barnabas were formally invested with this new commission by the laying on of hands and receiving the Holy Spirit (Acts 13:3). In Acts 14:23, St. Paul established presbyters (ordained priests) in every place on his return through Asia Minor on his first mission (Acts 14:23). In 1 Thess. 5: 12-13, he told the people to obey the religious authorities.

The apostles, and therefore their appointed successors in the priestly ministry, were given the power to “bind and loose” (Mt 18:18). The authority to bind and loose included administering and removing the temporal penalties due to sin. As Jews, the apostles would have understood this, for it was the power that the priests in the Temple had until then, which included defining divine revelation. Jesus ordained the apostles as priests at the Last Supper by performing the Levitical ordination ritual of the washing of feet (Jn 13:1-20). Jesus told Peter he couldn’t have a share in his priesthood or have a part of him (in persona) unless he allowed our Lord to wash his feet after he objected to this. Peter then replied by saying, ” Lord, not my feet only, but also my hands and my head.”

The washing of the head and hands was included in the Levitical ordination ceremony, but Jesus focused only on the washing of feet, which symbolized humility and service in the ministry. In the midst of the “consecration” of Aaron and his sons, Moses “washed them with water” (Lev 8:6-10). We also see Aaron and his sons washing their hands and their feet (Exodus 40:30-32). Moreover, the mention of having a “part” (meros) in John 13:8 recalls the priestly Levites having their portion (meris) in the LORD or in persona (Num 18:20; Deut 10:9, LXX).

Jesus concluded this part of the Last Supper by telling his apostles that they should do as he had just done in his ministry by being as humble and loyal in their commission, and he added, “Truly, truly, I say to you, he who receives whomever I send receives me; and he who receives me receives him who sent me” (Jn 13:20). Thus, Jesus did, in fact, transfer his priestly authority to his apostles, and they were to act in his name in persona Christi for the dispensation of his grace. With this authority, they could also ordain Matthias, Paul, Barnabas, and countless others who, in turn, would do the same up to our present day in the Catholic Church by the laying on of hands in an unbroken physical chain or line of apostolic succession through the Sacrament of Holy Orders.

Orally confessing sins to other people and not strictly privately to God was practiced and considered necessary in the infant Church and would continue in post-apostolic time in the early Church. James explicitly teaches us to “confess our sins to one another” (Jas 5:16). This passage must be read in context with Vv. 14-15, which refers to the physical and spiritual healing power possessed by the priests to whom we should confess our sins in the Sacrament of Reconciliation for the grace of forgiveness. Indeed, countless people came to the apostles and their anointed associates to orally confess their sins (Acts 19:18). They didn’t go home and confess their sins directly to God in private with indifference toward the divine authority of the apostles or elders and presbyters. The faithful practiced professing their faith and orally confessing their sins before human witnesses (1 Tim 6:12).

Our Lord faithfully cleanses and forgives us our sins provided we confess our sins to one another (1 Jn 1:9). Confessing one’s sin and making public restitution to re-enter the community of faith was a practice of the ancient Jews (Num 5:7). The Israelites stood before a public assembly to confess their sins and intercede for each other (Neh. 9:2-3; Baruch 1:14). In fact, God desired that His chosen people should confess their sins and not be ashamed to do it publicly (Sirach 4:26). Many people who came to John the Baptist at the Jordan river orally confessed their sins to him in a spirit of repentance and a firm desire for amendment (Mt: 3:6; Mk 1:5).

So, the Sacrament of Reconciliation has its roots in ancient Judaism. Mortal sins lead to spiritual death and must be absolved in the sacrament if we hope to be saved. Venial sins (that don’t incur spiritual death or cost us our salvation) don’t have to be confessed to a priest, but pious Catholics include them in the confessional in order to receive graces for spiritual growth in holiness and avoid entering or spending more time in purgatory (1 Jn 5:16-17; Lk 12:47-48).

Finally, repentance is incomplete if the debt of sin remains in the balance. God forgave David for his mortal sins of murder and adultery after he sincerely repented and confessed his sins with a contrite heart and broken spirit. But to offset his transgressions and restore equity of justice, God took the life of the child David conceived in his act of adultery with Bathsheba for having murdered her husband Uriah: an innocent life for an innocent life, or an eye for an eye. And God also permitted the rape of David’s wives for his act of adultery (2 Sam 12:9-10, 14, 18-19). Only then could David’s broken relationship with God be fully amended, provided he accepted his pain and loss as a temporal punishment for his sins to restore equity of justice in his relationship with God.

The debt of sin can be fully remitted only by having to do penance for it. Doing acts of penance, whose pain and loss counterbalance the sinful pleasure one is heartily sorry for, or accepting the pain and loss that God permits because of our sins, completes the temporal redemptive process. Christ didn’t suffer and die so that we should no longer owe God what is His rightful due for having offended His sovereign dignity (Mt 5:17; Job 42:6; Lam 2:14; Ezek 18:21; Jer 31:19; Rom 2:4; Rev 2:5, etc.). This is from Jesus himself: “No, I say to you: but unless you shall do penance, you shall all likewise perish”(Lk 13:3); “Bring forth, therefore, fruit worthy of penance” (Mt 3:8). True repentance for the forgiveness of sin calls for fruit worthy of our act of contrition. Our outward acts (almsgiving/fasting) must conform to our inner disposition or spiritual reality (charity/temperance) to offset our vices and sins (greed/gluttony), which have been forgiven by the act of contrition pending full temporal restitution. This is all part and parcel of our confession through the sacrament given to the Church by Christ Himself.

“In church, confess your sins, and do not come to your prayer with a guilty

conscience. Such is the Way of Life…On the Lord’s own day, assemble in common

to break bread and offer thanks; but first confess your sins, so that your [Eucharistic]

sacrifice may be pure.”

Didache, 4:14,14:1 (c. A.D. 90)

“Father who knowest the hearts of all, grant upon this Thy servant whom Thou

hast chosen for the episcopate to feed Thy holy flock and serve as Thine high

priest, that he may minister blamelessly by night and day, that he may

unceasingly behold and appropriate Thy countenance and offer to Thee the

gifts of Thy holy Church. And that by the high priestly Spirit he may have

authority to forgive sins…”

St. Hippolytus (A.D. 215)

Apostolic Tradition, 3

PAX VOBISCUM

Leave a comment